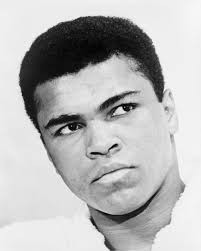

Is there another Muhammad Ali in Louisville, Dallas, New Orleans or Chicago?

Muhammad Ali didn’t emerge from empty space.

He represented the people and neighborhoods of Louisville.

We should assume there are more like him in Louisville, Dallas, New Orleans and Chicago. And our adulation of individuals should inspire community investment.

More institutions should see the cultivation of neighborhoods as a requisite of leadership development. Paul Quinn College is taking that approach through its new African American Leadership Institute.

Paul Quinn is literally harvesting the land so leadership naturally grows amongst those who cultivate it.

By pigeonholing leadership as individualistic and exceptional, we negate the power of parents, community members and neighborhoods that ostensibly produced greatness.

Therefore, we tend to remember the icons of leadership as being exceptional. Muhammad Ali for instance is widely cited as an “American original.” But leadership is more representational.

Michael Sorrell, president of Paul Quinn College, a historically black college in Texas, announced the launch of the African American Leadership Institute in a context in which many assume there is a void.

Most blacks in the Dallas Fort Worth area are concentrated with Hispanics within neighborhoods south of the Trinity River and I-30.

Income, health and quality of life disparities between blacks in South Dallas and their wealthier, white counterparts north of the river are as stark as in other metros.

There are events that illustrate social and economic divides in ways that numbers never can. Just this past May in the neighborhoods in and around Paul Quinn College, a 52 year-old woman was mauled by a pack of loose dogs, which proliferate the area. It’s hard to imagine a loose dog problem in a wealthy, white suburban enclave.

“If you live in the southern part of the city, you’re concerned with stray dogs,” said Sorrell while shaking is head in disbelief. “How preposterous is that?”

Loose dogs reflect the entrenched political disenfranchisement that results in an insufficient amount of public resources to meet basic needs of black and brown, low-income communities. But we should never assume that a lack of resources equates to a lack of leadership. Leadership emerges from opportunity. Moreover, communities can’t sit on their hands waiting for the sympathies of onlookers to incite social, political and economic uplift. The most equipped advocates for change come from the areas that need social improvements the most.

Paul Quinn has taken a prominent role in eradicating the stray dog problem in South Dallas. “If we don’t do these things, they are not getting done,” said Sorrell.

The African American Leadership Institute will leverage of power of place, elected officials, businesses as well as research to inspire leadership aimed at improving the conditions of blacks in neighboring South Dallas. Students will learn practical skills to enact promising public policies for immediate needs; expand job opportunities for low-income residents; increase access to quality schools and universities; and generate research that will inform the public.

The ethic of self-reliance already fuels many of the programs at Paul Quinn. “We believe that it’s necessary to address the issues of the community that we serve,” said Sorrell. “We are in a food desert so we turned the football field into a farm.”

Making education relevant not only motivates the student; he or she participates in the transformation of their own community.

In his eight years in the president’s seat, Sorrell developed a reputation of being relevant. In the face of poverty, Paul Quinn became the first urban work college in the country. Students attending Paul Quinn receive a job on or off campus that offsets tuition and living expenses. The designation allows Paul Quinn to cut $10,000 out of the cost of attendance and students can graduate with less than $10,000 in debt.

But Sorrell also realized that Texas has a “peculiar relationship with race.” Sorrell asked rhetorically, “How do you address the centuries old issues that are associated with being an African American in Texas?”

Authentic leadership in America has always been revealed in black – particularly young – people’s efforts to claim physical, political and social space within a country that still forces black folk to humbly accept already defined spaces as being good enough. Forged in a segregated America, historically black colleges and universities still create enough space for students to find themselves so that America can see what leadership really can be. Paul Quinn’s African American Leadership Institute is simply living out the original mission of HBCUs.

It’s similar to a then-controversial move Sorrell made early on in his tenure at Paul Quinn, when he cut the school’s football team. The football field is now a thriving organic community farm.

“Truthfully when I became a college president, I did not think I was going to turn a football field into a farm. I knew we were going to do health and wellness, but I thought we were going to build a state of the art fitness facility. But what was required was so much more basic than that,” Sorrell says.

However, Sorrell isn’t working in a vacuum. There is leadership living within the less than optimal neighborhood conditions of South Dallas. By focusing on these in your face ailments, students help their own cause by releasing the potential of all South Dallas residents.

What may seem simplistic and mundane is actually exceptional: The African American Leadership Institute aims to make Paul Quinn College a national leader in being a good neighbor.

This article was originally published on Is there another Muhammad Ali in Louisville, Dallas, New Orleans or Chicago?